|

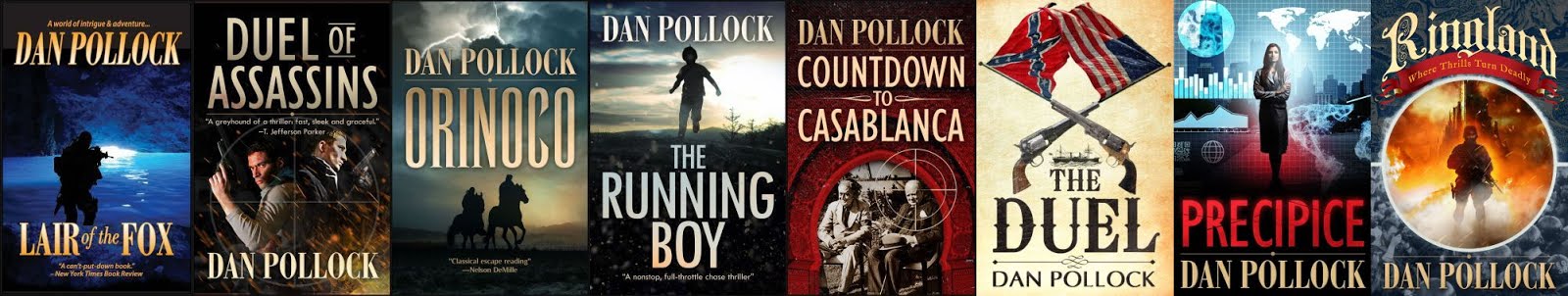

| Side by side--in my dreams! |

We’ve

all heard stories about how celebrated best-sellers were repeatedly rejected

before achieving their ultimate success and bringing untold pleasure to

millions of readers.

The

list of distinguished authors who struggled past initial rejections is

surprisingly long. It contains legendary names like John Grisham, John D.

MacDonald, Vince Flynn, Louis L’Amour, Tony Hillerman, Zane Grey, even J.K.

Rowling—and a whole lot more.

A

textbook case is that of Stephen King. His first novel, CARRIE, about a tormented

girl with telekinetic powers, racked up 30 rejections; whereupon its disheartened

creator tossed it in the trashbin. Only to have his wife fish it out and

prevail on him to send it around again.

A

textbook case is that of Stephen King. His first novel, CARRIE, about a tormented

girl with telekinetic powers, racked up 30 rejections; whereupon its disheartened

creator tossed it in the trashbin. Only to have his wife fish it out and

prevail on him to send it around again.

Shows

you the value of a “Yes, dear” marriage.

These

turnaround tales offer frustrated writers more than consolation; they are

endlessly inspiring. They tempt us to construct a syllogism along these lines:

Many

best-selling books were repeatedly rejected. My book has been

repeatedly rejected. Ergo, my book will be a best seller.

Alas,

99.99% of repeatedly rejected manuscripts do not become best-sellers. (But maybe if they’d been submitted just

one more time…)

Like

CARRIE, my first book, LAIR OF THE FOX, was repeatedly rejected, yet ultimately—after

I‘d abandoned all hope—was published. Alas, its sales trajectory and my

writing career did not continue to parallel CARRIE’s and Mr. King’s. Not

hardly.

And

yet there are some additional and interesting

parallels in the publication stories of LAIR and CARRIE.

I

started my writing career with at least one advantage over the schoolteacher

from Maine. When I began plotting and writing LAIR, I was working on the

copydesk of the L.A. Times Syndicate, under a managing editor who had worked

for some years as a successful book editor with a mainstream New York

publishing house.

With

some hesitancy, my boss agreed to look over my synopsis and three

chapters—the accepted formula at the time for any book submission. It took several weeks, and a few followup nudges from me, to get her actually to open

up the manila envelope I’d given her and read through my proposal, but in the

end she was enthusiastic and agreed to send it, along with a cover letter, to a

prominent New York agent.

This

woman, head of her own agency, sent me an encouraging note several weeks later.

I felt like Sally Field at the Oscars. Two savvy women in the book biz liked my

novel—they really did! The New York agent even invited me to meet her for

breakfast on her next West Coast swing at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel.

At

that meeting, she gave me some good suggestions; I nodded my head vigorously at

each one. “I can sell this,” she said, “but three chapters won’t do it. How

soon can you give me 100 pages?” A month? Two months? I can’t recall what

number I came up with. But, writing furiously before and after work and on

weekends, I met the deadline.

Then I

waited for the magic phone call.

What

I got instead—every few days, it seemed—were No. 10 envelopes from my New York

agent, each containing one or more Xeroxed rejection letters from big-time

editors at big-time publishing houses. Not form rejection letters, mind you,

but friendly notes to my agent, politely dismissing my book—for a puzzling variety of

reasons.

How

many major publishing houses were left? I wondered.

Then—hallelujah!—I

got a Xeroxed letter from a publisher with an enthusiastic cover note from my

agent. An executive editor at New American Library—a highly respected guy, she

wrote—was willing to consider

buying LAIR if the author would make

a certain story change—a pretty major change, with drastic ramifications

affecting the rest of the downstream plot.

I

telephoned her back and said yes. What the hell else could I say?

Then

I set to work. Reconstructing my intricate plot proved even trickier than I’d

imagined. The new structure kept collapsing. But, of course, it had to work. After several agonizing weeks

I managed to cobble together a new synopsis and send it off to my agent, who

forwarded it to the interested editor.

For

days and days I didn’t hear a thing. Finally I called to check. “You took too long,”

my agent admonished me. “He’s no longer at NAL, and his replacement isn’t

interested.”

When

the power of coherent speech returned to me, I asked her if she was going to

continue to send it out to other publishers. Sure, she said, but added that there

weren’t that many left on her list.

A few

weeks and several rejection slips later my New York agent phoned to say that she

was truly sorry, but she’d given it her best shot and there was nowhere else

she could send LAIR.

“Write

me something else,” she said.

So,

just like Stephen King, weary of seeing his beloved CARRIE turn up in his

mailbox yet again, I set LAIR OF THE FOX aside. Stuffed into a filebox, not the

trashbin, but it amounted to the same thing—a quick burial without ceremony. Despair

congealed around me like a straitjacket, but within a week I began plotting a

new story. “Something completely different,” as Monty Python used to say.

Clearly

I needed a new approach, a new voice, maybe a new niche. But my wife, like Stephen

King’s, hadn’t given up on my firstborn. And she had an idea.

An

interesting thing happened in book publishing just about then. The first in a

brand-new genre, the “techno-thriller,” Tom Clancy’s THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER, suddenly

shot to the top of the best-seller lists. The book bore an unlikely imprimatur—the

Naval Institute Press in Annapolis, Md. HUNT, it turned out, had been roundly

rejected by all the mainstream New York houses before finding its modest home.

An

interesting thing happened in book publishing just about then. The first in a

brand-new genre, the “techno-thriller,” Tom Clancy’s THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER, suddenly

shot to the top of the best-seller lists. The book bore an unlikely imprimatur—the

Naval Institute Press in Annapolis, Md. HUNT, it turned out, had been roundly

rejected by all the mainstream New York houses before finding its modest home.

Why

not, my wife asked, send LAIR OF THE ROX to the Naval Institute Press? And if

that doesn’t work, what about other second- and third-tier publishers,

university presses, and so on? What have you got to lose?

Of

course, she was right. When isn’t she? So I wrote my New York agent and politely

inquired—since she’d run out of places to submit LAIR—if she’d mind if I tried

to agent it myself. Starting with the Naval Institute Press.

Two

weeks passed without response. Okay, I thought, so I’m chopped liver, I’ll

just go ahead on my own. Finally she called me—to tell me she’d just sold the book.

“It's not

a major publisher,” she cautioned, “and not a big advance.”

I

didn’t care to whom or for how much, I’d finally sold a book! Well, she had, but it was my dream that had just come true at last! Thanks to my wife’s

advice, which had apparently prodded my agent into flipping beyond her favorite

section of her Rolodex.

At that

point I was scribbling the details—a small independent New York publisher,

Walker & Co., was offering $2,500 for LAIR. Would I take it? Yes, I would.

Walker

was giving me six months to finish it—remember, I’d written only 100 pages. No

problem, I told the agent. The rest would be easy. After several days of

celebrating and telling the good news to everyone I could think of, I set to

work.

I’m a

slow writer. Sometimes really slow—a

fact that had already cost me the NAL sale. Knowing that, my wife began measuring

my daily output against my six-month deadline. “You’ll never make it,” she concluded.

“Not even close. You need to ask for a leave of absence.”

She

showed me the math, and I saw she was right (what else is new?). I went to my

editorial bosses and begged; they understood what a big deal it was, bless

them, and a three-month leave was arranged. Even then, working full time—and double

time the last few weeks—I barely made it, rushing down to Fed-Ex on the final

afternoon.

My

editor was enthusiastic. He loved my writing, he said. There was only one slight

problem. The manuscript was too long. It turned out that Walker & Co., after

careful calculations of their manufacturing costs against pricing structure, was

forced to limit all their books to no more than 80,000 words.

LAIR

OF THE FOX weighed in at 120,000. So 40,000 of those words had to be removed.

I was

stunned, but my editor was treating this as no big deal. “If you like,” he said

in a helpful vein, “I can take care of it. I think I can find a couple chapters

you could do without.”

“No, please,

don’t do that!” I protested. “I’ll do

it. Just give me a week or two.”

So I

went through my precious, polished, perfect manuscript again—line by line and

word by word—with a predatory eye and a No. 2 draughting pencil. (For hints

about how best to do this, check out my blog post on Kipling’s “Higher Editing.”) The first pass

didn’t come close; radical surgery was needed. The second time through I became

reckless. Sentences vanished, then entire paragraphs; long scenes turned into vignettes.

I stopped just short of excising whole chapters, as my editor had so blithely

proposed.

When

I got to the magic number of 80,000 words, I Fed-Exed LAIR OF THE FOX-lite off

to my editor. “I couldn’t have done it better!” he generously conceded.

More

importantly, he thought the book was the better for the reductive process. He

was right. Rereading LAIR today, I don’t miss any of those well-chosen words

that aren’t there anymore.

Now

it was time to start marketing efforts, because my little publisher didn’t have

any budget for this, it turned out. Walker & Co. sold mostly to public

libraries.

So I

crafted letters to various thriller writers I admired, hoping to charm at least

one of them into reading, and favorably commenting on, an advance reading copy

or galley proof, when they became available.

These

were purely shot-in-the-dark letters, addressed to famous names in care of

their publishers. But two of these celebrity authors—Clive Cussler and the late

Ross Thomas—eventually wrote back and said they’d be happy to look at a galley.

Cussler gave me his address in Colorado, Thomas in Malibu.

Weeks

later, after I’d sent them copies of the first galleys, both these generous gentlemen

responded with timely endorsements which I use to this day.

My

editor was impressed with this, but told me that reviews were far more

important than author blurbs. “Keep your fingers crossed,” he said after the

review copies went out.

I’d

be lucky if LAIR OF THE FOX got reviewed at all, I thought. Why would Publishers Weekly, the New York Times, the L.A. Times et al., bother

with a title from little Walker & Co.?

But

they did. Not only that, they actually liked

it—that Sally Field thing again. Publishers

Weekly gave LAIR a starred review and pronounced it a “classic

can't-put-it-down thriller.” The N.Y.

Times and the L.A. Times provided

similar superlatives. Only Kirkus was snotty—“they always are,” I was told.

“Nobody pays attention.”

LAIR

OF THE FOX was starting to look like a contender.

Good

news continued. Not long after the hard cover was published (if you could find

it), reprint rights were sold to HarperCollins for its brand-new paperback

line. It wasn’t a financial bonanza, but several times what Walker had paid for

the hard cover, and I was now under the aegis of a prestige publisher.

As an

“added bonus,” in the tautology of the infomercial, the editor who bought my

book at Harper was the same guy who had

turned it down when he was editor-in-chief at another publishing house. I

had a copy of his earlier rejection letter and the original of his new

congratulatory letter to prove it!

“But

wait, there’s more” (another infomercial refrain). A month or so later the

agent sold my second “book”—this time only a 10-page synopsis and a brief

opening chapter—to another major publisher, Pocket Books, a division of Simon

& Schuster.

This

sale was a bonanza, at least in my

world. “Are you sitting down?” the agent said over the phone, preparing me for

her bombshell news. When I said I was, I heard those magic words I’d dreamed of

for so many years:

“You

can quit your job!”

Dizzy-making

details followed, all about the hard-soft contract and schedule of payouts. And

there was one final coincidence—the Pocket Books’ editor I’d be working with on

the new book was the same guy who

demanded I change the LAIR OF THE FOX plot back when he’d been at New American

Library.

There

aren’t many days like that, no matter what your profession. Considerable

detours and reverses were lurking farther down my writing career path—remember,

this is my story, not Stephen King’s or any of those other famous names’—but

I’ll leave the dreary negative stuff for another post. The good news is that I

did quit my job, and not long afterward my wife and I set off for a research

trip to Europe and even splurged a bit.

Moral?

One, for sure, is: Marry well—and listen to your spouse.

Postscript:

Thanks to the digital publishing revolution, LAIR OF THE FOX and my other titles

are now enjoying a second launching and are starting to build the kind of

readership that I always hoped for. The last chapter has not been written.

Flash

forward many years. I was wandering the bookstalls of London’s Heathrow Airport

looking for a paperback to help pass the 11 airborne hours from London to Los

Angeles. I settled on a Jack Higgins thriller titled Solo about a concert pianist who moonlighted as a contract

assassin. Seriously.

Flash

forward many years. I was wandering the bookstalls of London’s Heathrow Airport

looking for a paperback to help pass the 11 airborne hours from London to Los

Angeles. I settled on a Jack Higgins thriller titled Solo about a concert pianist who moonlighted as a contract

assassin. Seriously. Of

course I’d read, and watched, the collision course formula applied a thousand

times before, on TV, in movies and stories. Holmes vs. Moriarty, Superman vs.

Lex Luthor, Captain Marvel vs. Dr. Sivana, Batman vs. the Joker, North vs.

South, Cavalry vs. Indians. And in a thousand action movies—boxing, samurai,

spy vs. spy, even understudy vs. leading lady. Always the formula worked, but it

never coalesced in my mind as a story structure until Higgins’ Solo. When it did, it turned on a

lightbulb thought: “I want to write one of these!”

Of

course I’d read, and watched, the collision course formula applied a thousand

times before, on TV, in movies and stories. Holmes vs. Moriarty, Superman vs.

Lex Luthor, Captain Marvel vs. Dr. Sivana, Batman vs. the Joker, North vs.

South, Cavalry vs. Indians. And in a thousand action movies—boxing, samurai,

spy vs. spy, even understudy vs. leading lady. Always the formula worked, but it

never coalesced in my mind as a story structure until Higgins’ Solo. When it did, it turned on a

lightbulb thought: “I want to write one of these!” But

eventually it got written. More than a year later, I was able to hand an

advance reading copy to a colleague, best-selling mystery writer T. Jefferson

Parker (see my blog post, “A Good Writer Who Keeps Getting Better”) and ask him if he’d be willing to read it and maybe give me a quote.

But

eventually it got written. More than a year later, I was able to hand an

advance reading copy to a colleague, best-selling mystery writer T. Jefferson

Parker (see my blog post, “A Good Writer Who Keeps Getting Better”) and ask him if he’d be willing to read it and maybe give me a quote.