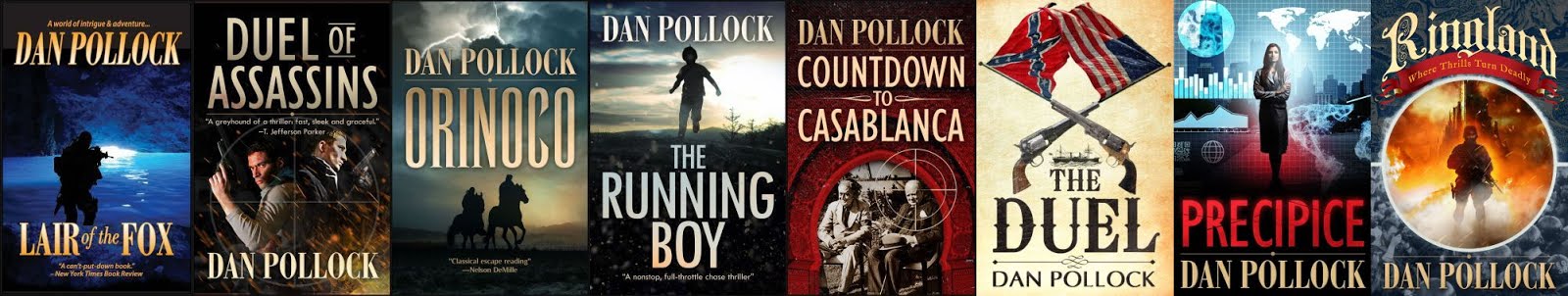

Looking

back, I can see a certain predestination in my becoming a thriller writer. I’ve

always loved the genre, for one. And my dad, the late Louis Pollock, was a

skillful practitioner thereof. With two stubby fingers on his big black typewriter he hammered out several “ticking-clock”

half-hour scripts for the old CBS Suspense radio show*—one of which Alfred

Hitchcock selected and directed on his half-hour TV series, Alfred Hitchcock

Presents.**

But

I took the long way around to Thrillerville. En route I tried my hand at all

sorts of categorical fiction, from sword and sorcery (influenced by Robert “Conan”

Howard), sci-fi (by Heinlein, Van Vogt, Sturgeon, among others), detectives and

mysteries (from Sherlock to L.A. Noir), even an overwrought Harlequin romance (Riviera

Concerto, unfinished, unfinishable). Somehow I missed YA.

But

I took the long way around to Thrillerville. En route I tried my hand at all

sorts of categorical fiction, from sword and sorcery (influenced by Robert “Conan”

Howard), sci-fi (by Heinlein, Van Vogt, Sturgeon, among others), detectives and

mysteries (from Sherlock to L.A. Noir), even an overwrought Harlequin romance (Riviera

Concerto, unfinished, unfinishable). Somehow I missed YA.

False

starts and dead-ends, all. True, I didn’t know how to plot, but that’s another issue.

None of these genres was a good fit for me. I could write passable short verse,

but my ambitions remained novelistic.

My

breakthrough, as I’ve mentioned before, was in confession stories, one of the remaining

magazine short story markets back in the '70s. It was all about the trials and

tribulations of young women—older teens, young marrieds, girls “in trouble.” I

was ill suited for this niche, too, but succeeded, I suspect, because my submissions

were actually suspense stories in drag.

Examples:

“Can’t Anyone Hear Me Crying?” (True Story); “We Drove Into Disaster” (True

Confessions).

Eventually and by default, I arrived at the pigeonhole where I felt most at

home—suspense/thrillers. My struggles continued; the apprenticeship was long

and bumpy, still is. But I like the terrain.

And

suspense is not really a sub-category of fiction. It is primal and primary, embodying

the essence of all good storytelling. I say “storytelling” because the oral tradition

precedes the written. The tribal bard, way back into prehistory, earned his keep by

capturing and holding an audience against stiff competition—an audience usually

exhausted by the day’s labor.

An

effective occupational imperative. Talk about "publish or perish." Spellbind your audience

or quit the campfire for the cold.

Scheherezade

had to keep the Sultan desperate to hear the next installment in order to

prolong her life one more night.

I’m

reminded of the Jma ’el Fna, a huge square of beaten earth in the center of

Marrakesh. It’s a meeting of ancient caravan routes, a legendary Arab-Berber

swap-meet, little changed over the centuries. You can still wander the stalls,

feasting on roasted mutton, and find snake charmers, sword-swallowers,

letter-writers and teeth-pullers along with sellers of T-shirts and pirated jeans

and DVDs, all competing for your coin.

Imagine,

if you will, a tale-teller among them, practicing his craft in the age-old way.

Enticing an audience, launching his tale, getting them “hooked,” stopping at a

cliff-hanger, then making his circuit, hat in hand. If he’s good, the listeners

will pay to hear the rest of the story. If they wander off to see the

fire-eater, he'd better brush up on his technique.

Dickens

had his readers so well and truly hooked that they crowded the New York City

docks to meet the ship from London with the next magazine installment of Copperfield

or Old Curiosity Shop. Of course, it was not just Dickens’ plot predicaments

that had them hanging. His characters were magically alive in his readers, in

suspended animation, waiting to get their next lines.

And

Dickens possessed another commodity rare in thrillerdom, and in modern fiction—narrative

charm. Which goes back to storytelling ability. Scheherezade obviously had it.

It’s a quality on display in every paragraph of Jane Austen, Robert Louis Stevenson,

Arthur Conan Doyle and many other beloved storytellers.

“I

feel that storytelling is the highest ambition of fiction,” thriller novelist AndrewKlavan said once in an interview with Publishers

Weekly (6/12/95). “Authors are storytellers first and foremost.”

“It

is just this power of holding the attention which forms the art of

story-telling,” wrote Conan Doyle, “an art which may be developed and improved

but cannot be imitated. It is the power of sympathy, the sense of the dramatic.

There is no more capricious and indefinable quality. The professor in his study

may have no trace of it, while the Irish nurse in the attic can draw out the

very souls of his children with her words. It is imagination—and it is the power

of conveying imagination.”

“Booth

Tarkington (1869-1946) told a reporter that when he worked on a story, he

imagined

that he was telling it to a man who had to catch a train in 20

minutes. The man was, of course, preoccupied with train-catching, impatient at

being buttonholed and very suspicious of his narrator—in fact, almost certain

that there would be no point to Tarkington's story... You see the precautions [Tarkington]

took against lapsing even for a paragraph into any dependence on the reader's

good will.” (Quoted by Gorham Munson in The Written Word, 1949, p. 20)

If

readers were distracted in Tarkington's era, think how much more addlepated

they are today. ADHD may be reaching epidemic proportions as our collective attentions

are assaulted by digitized stimuli inbound on radio, TV, iPhone and computer

screens, billboards and earbuds.

|

| Charles "Chuck" Braverman |

The

besieged modern audience is attuned not to gradual narrative unfolding, but to instant

visual and auditory overload. I trace the acute phase of this back to the ‘70s and

Chuck Braverman’s “American Time Capsule.” This was supposedly a short “film,” but

actually a linear mosaic of graphic images projected at epilepsy-inducing, stroboscopic

speed, compressing two hundred years of American history into two and a half

minutes.

No

wonder many of us like to escape with a good book, or e-book, or audiobook (ah, the oral tradition!). Despite all the environmental

static, the storyteller's task has not really changed from the day of the minstrel.

|

| Jim Patterson |

And

commercial thriller writing is storytelling at its most elemental. In the words

of a modern best-selling minstrel, James Patterson: “What I want to do right

now is write books that are satisfying to people who want to turn the pages.”

“Why

do we love suspense?" asked another such, John D. MacDonald. “The reader always

wants to know what happens next, whether he's reading The Brothers Karamazov,

David Copperfield or Hemingway.” (JDM, interview, Family Weekly, 5/5/85)

_______________________________________________________________

* “The Clock

and the Rope” starring Jackie Cooper (12.5.47); “A Ring for Marya” starring

Cornell Wilde (12.28.50); “Breakdown” (10.24.50)

** “Breakdown”

starring Joseph Cotton (11/13/1955).

No comments:

Post a Comment