The

title of this post is drawn from the autobiography of Rudyard Kipling, Nobel laureate, the second most quoted name

in English literature (according to Bartlett’s) after Shakespeare.

“Do

you like Kipling?” goes the old joke.

Answer:

“I don’t know, you naughty boy, I’ve never kippled.”

But

I’ll get back to Rudyard in a moment. First a plug from our sponsor, namely me.

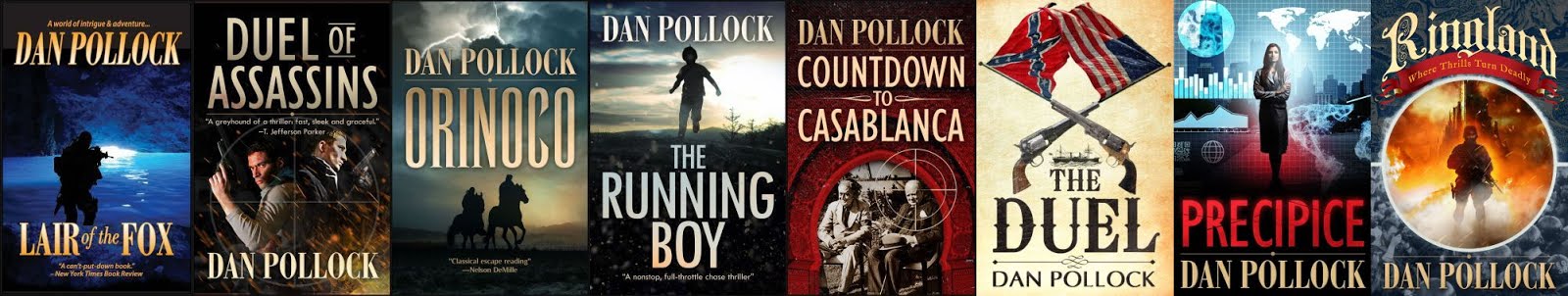

My

chase thriller, The Running Boy, can be downloaded in Kindle format free for

the next three days – Friday, Saturday and Sunday. I’m hoping to drum up some

interest, obviously, for what I consider an exciting read. So spread the word,

if you will.

You

can read an online interview with the author about the writing of The Running Boy here.

By

the way, on Monday and Tuesday Amazon will be giving away my most popular

thriller, Lair of the Fox. After that, both return to their regular Kindle

price of $2.99.

And

now back to our regularly scheduled post and Rudyard Kipling’s “Higher Editing”…

*

Kipling

flashed across the London literary firmament like a comet at age 23 with the

delicious short story collection, Plain

Tales From the Hills, followed a year later by Barrack-Room Ballads, which showed

him a master versifier.

But

the shooting star did not flame out. While he continued to produce stories and

poems at a prodigious rate, he never joined his own rabid fan club. He was certainly

aware of his genius, but his approach to the craft of writing remained ever that

of a conscientious workman. He edited himself ruthlessly.

“Higher

Editing” he called it, and I’ll get to the specifics of his technique in a few

moments.

But

please note: It is possible to expand a story or novel through good editing. To

diagnose what is lacking and suggest the addition of needed material.

That is emphatically not the kind of self-editing I’m talking about here. I’m talking “less

is more,” a strictly reductive process.

Wolfe's great big doorstop novels—Look Homeward, Angel, You Can’t Go Home Again, Of

Time and the River—all landed on Perkins’ desk as cartonloads of verbal

tonnage, all requiring major surgery. For instance, from the brilliant but bloated manuscript of Angel, Perkins managed to remove 90,000

words.

I

have a similar tale, with far punier statistics. My first thriller, Lair of the Fox, was sold on the basis

of an outline and the first 100 pages to a small publisher. The completed

manuscript weighed in at 120,000 words – every one them perfect, I'll have you know.

So

I was shocked to learn from my editor that this small publishing house (Walker

& Co.), in order to reduce their printing and binding costs, never

published trade books over 80,000 words. Therefore--would I please cut 40,000

words from my manuscript.

I

did it. And I relied on Kipling’s “Higher Editing” method to do it. And the book is much the

better for it.

It

wasn’t easy. As a legendary teacher of fiction writing once explained, “This is why surgeons never operate on members of their own family and

dislike to work even on close friends.” (William Foster-Harris, The Basic

Patterns of Plot, p. 112)

A

famous American editor has his own take: “Play ‘digester’ to your manuscript;

imagine that you are an editorial assistant on a digest magazine performing a

first squeeze on the article to be digested. Can you squeeze out an unnecessary

hundreds words from each thousand in your draft?” (Gorham Munson, The Written Word, p. 170)

John

D. MacDonald used the reductive process as an intrinsic part of his creative plan. A magazine profile

of the mystery master described him “tapping out the 1,000-page drafts that he

whittles down to 300-page manuscripts in four months.” (Newsweek, March 22,

1971, p. 103)

For

this reductive process to work, however, you have to put your heart

and soul into that first draft, like Tom Wolfe or John MacDonald. Don’t edit

or second guess yourself the first time through; let yourself be driven forward by the

compelling emotion of your story; to switch metaphors, trowel on the raw pigment, which you

can shape later at leisure.

To

quote Gorham Munson again, “Write as a writer, rewrite as a reader.”

(The Written Word, p. 167)

Another

master of mystery, Elmore Leonard, went from a journeyman paperback writer (westerns

and detectives) to best-sellerdom and Hollywood fame by taking an opposite tack. He began to

edit himself in advance — on his first draft. As he famously put it (his rule

No. 10 of good writing): “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”

If

you can do that, bravo! Others, some very great writers among them, have had to go

back over their work and painfully cut out the deadwood.

Here

is the method used by Georges Simneon, whom I profiled in an earlier post..

“In

response to the imperious instruction given him by Colette, "Suppress all

literature," he embarked on developing the pared-down style which he made

so notably his own." (“About Simenon,” The European, Nov. 2, 1990)

INTERVIEWER:

"What do you mean by 'too literary'? What do you cut out, certain kinds of

words?"

SIMENON:

"Adjectives, adverbs, and every word which is there just to make an

effect. Every sentence which is there just for the sentence. You know, you have

a beautiful sentence—cut it. Every time I find such a thing in one of my novels

it is to be cut." (Simenon quoted in Writers At Work, The Paris Review

Interviews, p. 146)

To quote Leonard again, “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

Granted,

that rule does not apply to the beloved storytellers of an earlier era—to Jane

Austen or Dickens, to Tolstoy or Conrad. Nor even to my favorite of current

thriller writer, Frederick Forsyth. Narrative charm is a special skill of selected yarn-spinners,

an honor to be conferred by adoring readers.

Granted,

that rule does not apply to the beloved storytellers of an earlier era—to Jane

Austen or Dickens, to Tolstoy or Conrad. Nor even to my favorite of current

thriller writer, Frederick Forsyth. Narrative charm is a special skill of selected yarn-spinners,

an honor to be conferred by adoring readers.

So,

at last, we come to Kipling’s “Higher Editng.” Here he describes how he used it

on his debut story collection, Plain Tales From the Hills:

“They

[Anglo-Indian tales] were originally much longer than when they appeared, but

the shortening of them, first to my own fancy, after rapturous re-readings, and

the next to the space available, taught me that a tale from which pieces have

been raked out is like a fire that has been poked. One does not know that the

operation has been performed, but everyone feels the effect...

This

leads me to the Higher Editing. Take of well-ground Indian Ink as much as suffices and a camel-hair brush proportionate to the interspaces

of your lines. In an auspicious hour, read your final draft and consider

faithfully every paragraph, sentence and word, blacking out where requisite.

Let it lie by to drain as long as possible. At the end of that time, re-read

and you should find that it will bear a second shortening. Finally, read it

aloud alone and at leisure. Maybe a shade more brushwork will then indicate or

impose itself. If not, praise Allah and let it go, and "when thou hast

done, repent not."... The magic lies in the Brush and the Ink.” (Rudyard

Kipling, Something of Myself, p. 224-225)

Another notion recently popped into my brain. How about being a fly on the wall in the Writers’ Room at Sid Caesar’s old “Your Show of Shows,” which,

as Wikipedia states, was “a live 90-minute variety show that was broadcast weekly in the

United States on NBC (Saturdays, 9:00-10:30 p.m. Eastern Time/6:00-7:30 p.m.

Pacific Time), from February 25, 1950, until June 5, 1954...”

Another notion recently popped into my brain. How about being a fly on the wall in the Writers’ Room at Sid Caesar’s old “Your Show of Shows,” which,

as Wikipedia states, was “a live 90-minute variety show that was broadcast weekly in the

United States on NBC (Saturdays, 9:00-10:30 p.m. Eastern Time/6:00-7:30 p.m.

Pacific Time), from February 25, 1950, until June 5, 1954...”