|

| Plot Outline Map from Hollywood Story Structure Guru Robert McKee |

Then there are the rest of us, writers

who, like me, need to build an elaborate track and know exactly where they’re

going, or they end up nowhere. Or stranded, at some accidental and inconclusive

terminus.

That’s happened to me—especially during the long, frustrating years of my apprenticeship—more times than I want to count. In my garage are stacks of cardboard boxes full of false starts and miscarriages, some of them hundreds of pages long. There’s even some good writing in those fragmentary projects, but so what? It’s all overdue for the recycling bin.

|

| Elmore Leonard |

But what about the “naturals”? How does yarn-spinning work for them?

The world recently lost one of these

naturally gifted storytellers, Elmore Leonard, a writer who never outlined or

plotted in advance. Here’s how he once

explained his process:

“Most thrillers are based on a situation, or on a plot, which is the

most important element in the book. I don't see it that way. I see my

characters as being most important, how they bounce off one another, how they

talk to each other, and the plot just sort of comes along.”

In fact, “Mr. Leonard is so comfortable

allowing his characters to control the pace and action of his stories that he didn't

know how Bandits would end until three

days before he finished it.” (Elmore Leonard quoted by Michael Ruhlman, New York Times Book Review, Jan. 4, 1987)

|

| Joe Wambaugh |

“I sort of relegate plot a little bit down on the list of importance in my mind. I don't really have an outline when I start a book. If I did, it wouldn't be any good. I create characters and, if you're really cooking, they take over. They direct you. You follow them.” (Joe Wambaugh interviewed in the San Diego Reader, Nov. 4, 1993)

|

| Howard & Frazetta's Conan |

|

| Stephen King |

"For

me, it's the idea [that comes first]. The characters are a perfect blank.

Everything about the character is a blank... the first thing that comes is the

situation, and the next thing that comes are characters that will fulfill that

situation." (Stephen King, Writer's

Digest, March 1992, p. 24 & 25)

|

| Dickens |

I suspect that even sly old Elmore Leonard

had an inkling of where he was letting himself be led. John D. MacDonald, whom

I have quoted so often in past posts, once described a novel-writing process

that sounds to me like a hybrid between plot-and-character driven:

|

| JDM |

So—to plot or not to plot, that is

the question. It would seem there are two equally valid answers. But for me, alas,

there is only one.

*

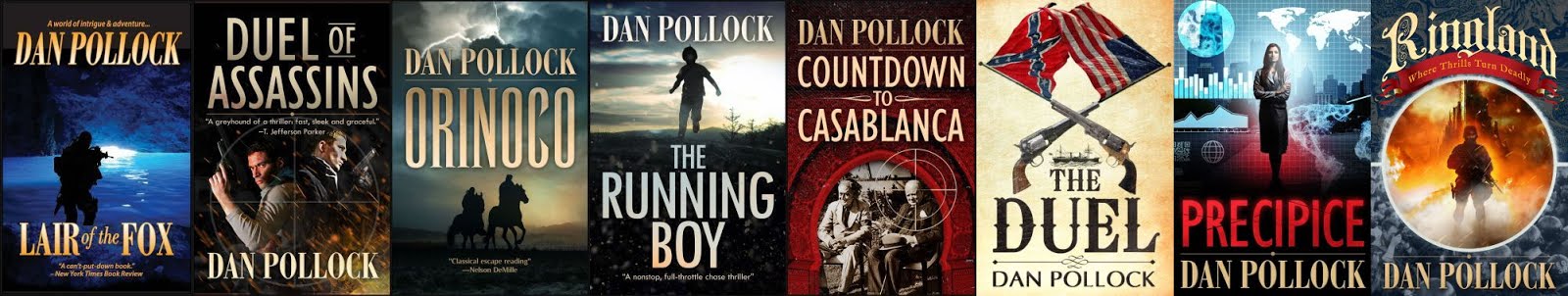

Up top I described myself as one of those

“who need to build a track and know exactly where they’re going, or they end up

nowhere.” A writer friend of mine put it this way: “Learning to write is track-laying. Writing is running on the track.

What people are always trying to do is run without a track.”

In subsequent

posts, I’ll talk about how I eventually learned to lay that story track. The

learning process, for me, was methodical and laborious, but utterly essential,

lacking as I did (and still do) that unerring narrative gift or instinct with

which some writers are so wonderfully endowed. And, as I say, careful plotting

is still essential for me, all these years and novels later. Novel construction

has not gotten noticeably easier. Each new project I undertake, like the

building of a house, requires careful blueprinting and frequent piece-by-piece inspections

to assure solid story structure with satisfying character trajectories, plot

tendencies, resolutions, declining action and so forth.

And I suspect I’m not alone in my

predicament. So, if you are like me, stay tuned to this space as I pass along

some hard-won tips on plotting, from short stories to long-form novels.

-page-001.jpg)