The Kindle Books and Tips blog has been ranked the #1 blog in terms of paid subscriptions in the Amazon Kindle store since 2010, and is consistently ranked in the Top 100 for all Kindle titles week in and week out. If you would like to have the blog’s posts sent to your email, you can subscribe here, or via e-Ink direct to you Kindle, you can click here

Monday, September 23, 2013

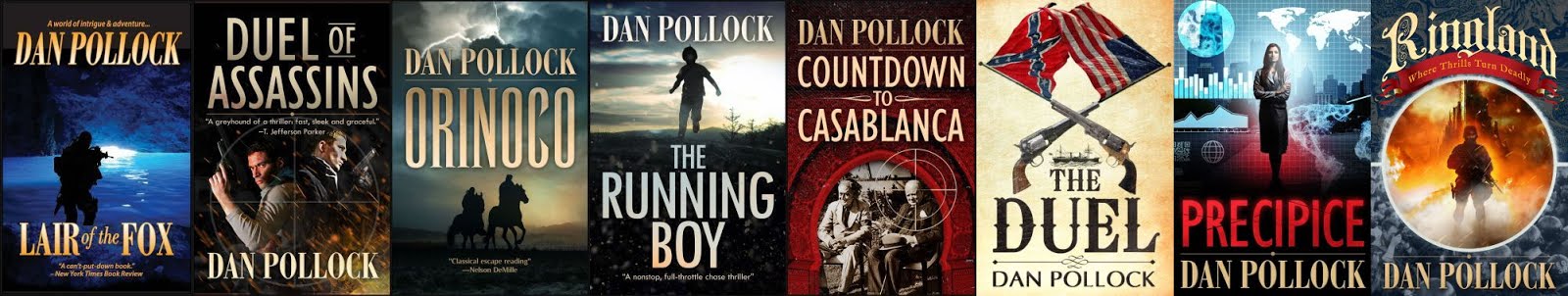

LAIR OF THE FOX FEATURED ON KINDLE BOOKS AND TIPS BLOG

The Kindle Books and Tips blog has been ranked the #1 blog in terms of paid subscriptions in the Amazon Kindle store since 2010, and is consistently ranked in the Top 100 for all Kindle titles week in and week out. If you would like to have the blog’s posts sent to your email, you can subscribe here, or via e-Ink direct to you Kindle, you can click here

Thursday, July 25, 2013

DESCRIBING STUFF

Your characters

are obviously more important than their settings, but there is a critical and creative synergy between character and setting--a synergy that takes place in the reader’s brain.

The late, great John D. MacDonald codified it this way: "When the environment is

less real, the people you put into that environment become less believable, and

less interesting."

He

illustrated his point with two descriptive passages. Here is the first:

“The

air conditioning unit in the motel room window was old and somewhat noisy.” MacDonald

called this an image cut out of gray paper. It triggers no vivid visual image.

By

contrast, see what happens in the imagination while reading this passage:

"The

air conditioning unit in the motel room had a final fraction of its name left,

an 'aire' in silver plastic, so loose that when it resonated to the coughing

thud of the compressor, it would blur. A rusty water stain on the green wall

under the unit was shaped like the bottom half of Texas. From the stained grid,

the air conditioner exhaled its stale and icy breath into the room, redolent of

chemicals and of someone burning garbage far, far away."

From

these close-up clues, MacDonald said, you the reader can construct the rest of

the room--bed, carpeting, shower, with vivid pictures from your own experience.

The

trick is how much to describe--the telling detail--and what to leave out. Too

much detail and you turn the reader into a spectator, no longer part of the

creative partnership whereby the reader fills in the rest of the scene out of

experience and imagination.

“No

two readers will see exactly the same motel room,” he added. But “the pictures

you have composed in your head are more vivid than the ones I would try to

describe.”

Note

that MacDonald did not label the air conditioner as old or noisy or battered or

cheap. Those are all subjective words, evaluations that the reader should make.

“Do not say a man looks seedy. That is a judgment, not a description. All over

the world, millions of men look seedy, each one in his own fashion. Describe a

cracked lens on his glasses, a bow fixed with stained tape, an odor of old

laundry.”

Note

also that MacDonald is using sensory cues in his quick sketch of the air

conditioner. You not only see the bottom half of Texas, you smell the burning

garbage, you hear the coughing thud.

There

are many masters of detailed description. One that comes to mind is the late

Joseph Hansen, author of the David Brandstetter mysteries. Here is an example,

picked almost at random from his 1973 novel, Death Claims:

“…The

front wall was glass for the view of the bay. It was salt-misted, but it let

him see the room. Neglected. Dust blurred the spooled maple of furniture that

was old but used to better care. The faded chintz slipcovers needed straightening.

Threads of cobwebs spanned lapshades. And on a coffee table stood plates soiled

from a meal eaten days ago—canned roast-beef hash, ketchup—dregs of coffee in a

cup, half a glass of dead, varnish liquid…”

It’s

clearly of a piece with MacDonald’s example. But Hansen, a poet as well as novelist,

seems to describe everything, every setting, every character, with such laser-like attention to detail, while

MacDonald picks his spots. For me as a reader, exhaustive detail is exhausting.

There

are celebrated passages, of course, where an author intends to glut the reader

with overflowing detail. A famous example occurs in Gustave Flaubert’s

descriptions of Madame Bovary’s wedding, in which every costume and every menu

course is lavished with loving prose:

“Upon [the table] there stood four

sirloins, six dishes of hashed chicken, stewed veal, three legs of mutton and,

in the centre, a comely roast sucking-pig flanked with four hogs-puddings

garnished with sorrel. At each corner was a decanter filled with spirits. Sweet

cider in bottles was fizzling out round the corks, and every glass had already

been charged with wine to the brim. Yellow custard in great dishes, which would

undulate at the slightest jog of the table, displayed on its smooth surface the

initials of the wedded pair in arabesques of candied peel…”

MacDonald

cites another exception to the less-is-more dictum: “In one of the Franny and

Zooey stories, [J.D.] Salinger describes the contents of a medicine cabinet

shelf by shelf in such infinite detail that finally a curious monumentality is

achieved…”

*

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

ORINOCO NOW PUBLISHED ON KINDLE

As a happy postscript to the previous, Orinoco is now available on Kindle and in paperback through Lulu.

As a happy postscript to the previous, Orinoco is now available on Kindle and in paperback through Lulu.Even better news, Orinoco will be FREE for download this coming Saturday and Sunday, July 13 and 14.

I quoted Tom Keneally's blurb on the previous post. Here are a few more I was tickled to get for this adventurous thriller:

"I never give quotes for fiction books, but Dan Pollock is a writer of talent and drive. His Orinoco is a riveting read." --Len Deighton

"Vivid and unforgettable..." --Liz Smith, syndicated columnist

"The mining of iron ore in thejungles of Venezuela is hampered by archaeological finds, and we have the ingredients of a good old-fashioned action-adventure story. Dan Pollock brings the reader right into the exotic locale and peoples his story with interesting characters. A well-written and obviously well-researched novel; classical escape reading."--Nelson DeMille

Thursday, July 4, 2013

A RIGHTFUL TITLE RESTORED

I was

informed, but not consulted. I felt like a parent watching helplessly through the hospital nursery window

as the nametag is switched on the bassinet bearing his child. Orinoco was thus born into the book world as Pursuit Into Darkness. With this eminently forgettable dust jacket over its face, the novel was barely promoted, scarcely noticed and soon forgotten.

The

brilliant Australian novelist Thomas Keneally captured my feelings perfectly

when he called me from “Oz” just about that time with his solicited endorsement. He had read an early proof of Orinoco and was properly disdainful when I told him of the last-minute name change. He

dictated his blurb thus:

The

brilliant Australian novelist Thomas Keneally captured my feelings perfectly

when he called me from “Oz” just about that time with his solicited endorsement. He had read an early proof of Orinoco and was properly disdainful when I told him of the last-minute name change. He

dictated his blurb thus:“What a ripping read. Orinoco--or by whatever meaningless name it is now being called--is a rapidly moving, thoroughly satisfying opus, good for a winter’s night or a summer’s day.”

Flash

forward a bunch of years to the present era of self- and independent

publishing. In my case (and in the case of many another published writer), it affords the glorious opportunity to republish out-of-print titles—and do it right

this second time around.

This time no committee, no finger-to-the-wind marketing manager, gets to rename

my opus. This is why I am particularly excited about the imminent independent publication

of PURSUIT INTO DARKNESS ORINOCO. In a couple weeks, it

will be available under its rightful and original name, and be judged by its proper

merits.

You see, the title was the book at its inception. I began not with an idea, but just that rhythmically

resonant name. Other tributaries of the story flowed into that riverine trunk.

As I mentioned in a previous post, among my early inspirations was Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, though I

skipped the dinosaurs that Doyle’s imagination deposited atop Auyán-Tepui, the giant sandstone mesa from whose prow Angel Falls plunges endlessly

down into the surrounding Venezuelan jungle.

You see, the title was the book at its inception. I began not with an idea, but just that rhythmically

resonant name. Other tributaries of the story flowed into that riverine trunk.

As I mentioned in a previous post, among my early inspirations was Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, though I

skipped the dinosaurs that Doyle’s imagination deposited atop Auyán-Tepui, the giant sandstone mesa from whose prow Angel Falls plunges endlessly

down into the surrounding Venezuelan jungle. Now I've just reread my manuscript for this South American thriller and discover that it's good! In fact, I have to agree with Nelson DeMille's generous plaudit: "A well-written and obviously well-researched novel; classical escape reading." (Thank you again, Mr. DeMille!)

Now I've just reread my manuscript for this South American thriller and discover that it's good! In fact, I have to agree with Nelson DeMille's generous plaudit: "A well-written and obviously well-researched novel; classical escape reading." (Thank you again, Mr. DeMille!)

I can hardly wait until Orinoco is reborn and rechristened on Kindle (and in Lulu print-on-demand). In fact, I'm going to be giving copies away, in lieu of cigars, as soon as they emerge from their digital womb.

Stay tuned for the official birth announcement!

Thursday, June 27, 2013

SPECTATOR TIME TRAVEL: POSTSCRIPT

Three months back, in a post called “SPECTATOR TIME TRAVEL,” I posed the hypothetical, “If you could be whisked backward in time,

by some Dickensian spirit or H. G. Wellsian device, where and when would you

go?”

I offered a grab bag of suggestions off the top of my head—attending

one of Charles Dickens’ legendary readings; sneaking into Sergei Rachmaninoff’s

Beverly Hills home back in the '30s and '40s to listen to the composer and his

dear friend, Vladimir Horowitz, play through the “Rach 3” on dovetailed concert

grands; or, maybe even more exciting,

one of the legendary “cutting contests” matching stride piano players such as

Fats Waller, Teddy Wilson, Count Basie, and Earl "Fatha" Hines.

It’s not that I wouldn’t want to be among the select few for the Sermon

on the Mount or at the foot of Sinai when Moses came on down with the Ten Commandments;

but Hollywood has already been there and done those, and the Gettysburg Address, tool.

Another notion recently popped into my brain. How about being a fly on the wall in the Writers’ Room at Sid Caesar’s old “Your Show of Shows,” which,

as Wikipedia states, was “a live 90-minute variety show that was broadcast weekly in the

United States on NBC (Saturdays, 9:00-10:30 p.m. Eastern Time/6:00-7:30 p.m.

Pacific Time), from February 25, 1950, until June 5, 1954...”

Another notion recently popped into my brain. How about being a fly on the wall in the Writers’ Room at Sid Caesar’s old “Your Show of Shows,” which,

as Wikipedia states, was “a live 90-minute variety show that was broadcast weekly in the

United States on NBC (Saturdays, 9:00-10:30 p.m. Eastern Time/6:00-7:30 p.m.

Pacific Time), from February 25, 1950, until June 5, 1954...”

The main comedy quartet--Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, Carl Reiner and Howard

Morris--was brilliant in skit ensembles. But behind them was marshaled perhaps an even

more awesomely talented team of comedy writers.

At various times (and, actually, on various Caesar shows), the all-star

lineup of jokemeisters included Mel Tolkin, Sir Caesar, Carl Reiner, Larry

Gelbart, Mel Brooks, Woody Allen, Neil Simon, Danny Simon, Sheldon Keller, Mel

Tolkin, Gary Belkin and Aaron Ruben.

To our great good fortune all these decades later, some Spectator Time Travel is possible in this case. You can purchase

a (somewhat pricey) DVD of “Caesar’s Writers” on Amazon.

Here’s the caption:

"On January 24, 1996 at the Writers Guild Theater in Los Angeles, CA, legendary comic Sid Caesar was reunited with nine of his writers from Your Show of Shows and Caesar’s Hour. The event was taped, and later broadcast on PBS in the United States, and the BBC in the UK as a 1 hour special, with only select portions of the full two-hour event. The full event was previously available only as a VHS, offered as a pledge premium by local PBS stations. Now, the full two-hour special CAESAR’S WRITERS is available on DVD for the first time! Be prepared to laugh non-stop as the panel, made up of head writer Mel Tolkin, Caesar, Carl Reiner, Aaron Ruben, Larry Gelbart, Mel Brooks, Neil Simon, Danny Simon, Sheldon Keller, and Gary Belkin share stories about their time working on Caesar’s shows and offer their insights about writing comedy..."

Thursday, June 6, 2013

HIGHER EDITING

The

title of this post is drawn from the autobiography of Rudyard Kipling, Nobel laureate, the second most quoted name

in English literature (according to Bartlett’s) after Shakespeare.

“Do

you like Kipling?” goes the old joke.

Answer:

“I don’t know, you naughty boy, I’ve never kippled.”

But

I’ll get back to Rudyard in a moment. First a plug from our sponsor, namely me.

My

chase thriller, The Running Boy, can be downloaded in Kindle format free for

the next three days – Friday, Saturday and Sunday. I’m hoping to drum up some

interest, obviously, for what I consider an exciting read. So spread the word,

if you will.

You

can read an online interview with the author about the writing of The Running Boy here.

By

the way, on Monday and Tuesday Amazon will be giving away my most popular

thriller, Lair of the Fox. After that, both return to their regular Kindle

price of $2.99.

And

now back to our regularly scheduled post and Rudyard Kipling’s “Higher Editing”…

*

Kipling

flashed across the London literary firmament like a comet at age 23 with the

delicious short story collection, Plain

Tales From the Hills, followed a year later by Barrack-Room Ballads, which showed

him a master versifier.

His

sensational debut at such a young age was comparable to that of Charles

Dickens. "The star of the hour," said Henry James when Rudyard was

only 25. "Too clever to live," said Robert Louis Stevenson.

But

the shooting star did not flame out. While he continued to produce stories and

poems at a prodigious rate, he never joined his own rabid fan club. He was certainly

aware of his genius, but his approach to the craft of writing remained ever that

of a conscientious workman. He edited himself ruthlessly.

“Higher

Editing” he called it, and I’ll get to the specifics of his technique in a few

moments.

But

please note: It is possible to expand a story or novel through good editing. To

diagnose what is lacking and suggest the addition of needed material.

That is emphatically not the kind of self-editing I’m talking about here. I’m talking “less

is more,” a strictly reductive process.

The most famous editor I recall hearing about was the legendary Maxwell Perkins,

editor and hand-holder of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe. Not our Tom

Wolfe, but the great undisciplined contemporary of Hemingway and Fitzgerald “whosetalent was matched only by his lack of artistic self-discipline.”

Wolfe's great big doorstop novels—Look Homeward, Angel, You Can’t Go Home Again, Of

Time and the River—all landed on Perkins’ desk as cartonloads of verbal

tonnage, all requiring major surgery. For instance, from the brilliant but bloated manuscript of Angel, Perkins managed to remove 90,000

words.

I

have a similar tale, with far punier statistics. My first thriller, Lair of the Fox, was sold on the basis

of an outline and the first 100 pages to a small publisher. The completed

manuscript weighed in at 120,000 words – every one them perfect, I'll have you know.

So

I was shocked to learn from my editor that this small publishing house (Walker

& Co.), in order to reduce their printing and binding costs, never

published trade books over 80,000 words. Therefore--would I please cut 40,000

words from my manuscript.

I

did it. And I relied on Kipling’s “Higher Editing” method to do it. And the book is much the

better for it.

It

wasn’t easy. As a legendary teacher of fiction writing once explained, “This is why surgeons never operate on members of their own family and

dislike to work even on close friends.” (William Foster-Harris, The Basic

Patterns of Plot, p. 112)

A

famous American editor has his own take: “Play ‘digester’ to your manuscript;

imagine that you are an editorial assistant on a digest magazine performing a

first squeeze on the article to be digested. Can you squeeze out an unnecessary

hundreds words from each thousand in your draft?” (Gorham Munson, The Written Word, p. 170)

John

D. MacDonald used the reductive process as an intrinsic part of his creative plan. A magazine profile

of the mystery master described him “tapping out the 1,000-page drafts that he

whittles down to 300-page manuscripts in four months.” (Newsweek, March 22,

1971, p. 103)

For

this reductive process to work, however, you have to put your heart

and soul into that first draft, like Tom Wolfe or John MacDonald. Don’t edit

or second guess yourself the first time through; let yourself be driven forward by the

compelling emotion of your story; to switch metaphors, trowel on the raw pigment, which you

can shape later at leisure.

To

quote Gorham Munson again, “Write as a writer, rewrite as a reader.”

(The Written Word, p. 167)

Another

master of mystery, Elmore Leonard, went from a journeyman paperback writer (westerns

and detectives) to best-sellerdom and Hollywood fame by taking an opposite tack. He began to

edit himself in advance — on his first draft. As he famously put it (his rule

No. 10 of good writing): “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”

If

you can do that, bravo! Others, some very great writers among them, have had to go

back over their work and painfully cut out the deadwood.

Here

is the method used by Georges Simneon, whom I profiled in an earlier post..

“In

response to the imperious instruction given him by Colette, "Suppress all

literature," he embarked on developing the pared-down style which he made

so notably his own." (“About Simenon,” The European, Nov. 2, 1990)

INTERVIEWER: "What do you mean by 'too literary'? What do you cut out, certain kinds of words?"SIMENON: "Adjectives, adverbs, and every word which is there just to make an effect. Every sentence which is there just for the sentence. You know, you have a beautiful sentence—cut it. Every time I find such a thing in one of my novels it is to be cut." (Simenon quoted in Writers At Work, The Paris Review Interviews, p. 146)

To quote Leonard again, “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

Granted,

that rule does not apply to the beloved storytellers of an earlier era—to Jane

Austen or Dickens, to Tolstoy or Conrad. Nor even to my favorite of current

thriller writer, Frederick Forsyth. Narrative charm is a special skill of selected yarn-spinners,

an honor to be conferred by adoring readers.

Granted,

that rule does not apply to the beloved storytellers of an earlier era—to Jane

Austen or Dickens, to Tolstoy or Conrad. Nor even to my favorite of current

thriller writer, Frederick Forsyth. Narrative charm is a special skill of selected yarn-spinners,

an honor to be conferred by adoring readers.

So,

at last, we come to Kipling’s “Higher Editng.” Here he describes how he used it

on his debut story collection, Plain Tales From the Hills:

“They [Anglo-Indian tales] were originally much longer than when they appeared, but the shortening of them, first to my own fancy, after rapturous re-readings, and the next to the space available, taught me that a tale from which pieces have been raked out is like a fire that has been poked. One does not know that the operation has been performed, but everyone feels the effect...This leads me to the Higher Editing. Take of well-ground Indian Ink as much as suffices and a camel-hair brush proportionate to the interspaces of your lines. In an auspicious hour, read your final draft and consider faithfully every paragraph, sentence and word, blacking out where requisite. Let it lie by to drain as long as possible. At the end of that time, re-read and you should find that it will bear a second shortening. Finally, read it aloud alone and at leisure. Maybe a shade more brushwork will then indicate or impose itself. If not, praise Allah and let it go, and "when thou hast done, repent not."... The magic lies in the Brush and the Ink.” (Rudyard Kipling, Something of Myself, p. 224-225)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

-page-001.jpg)